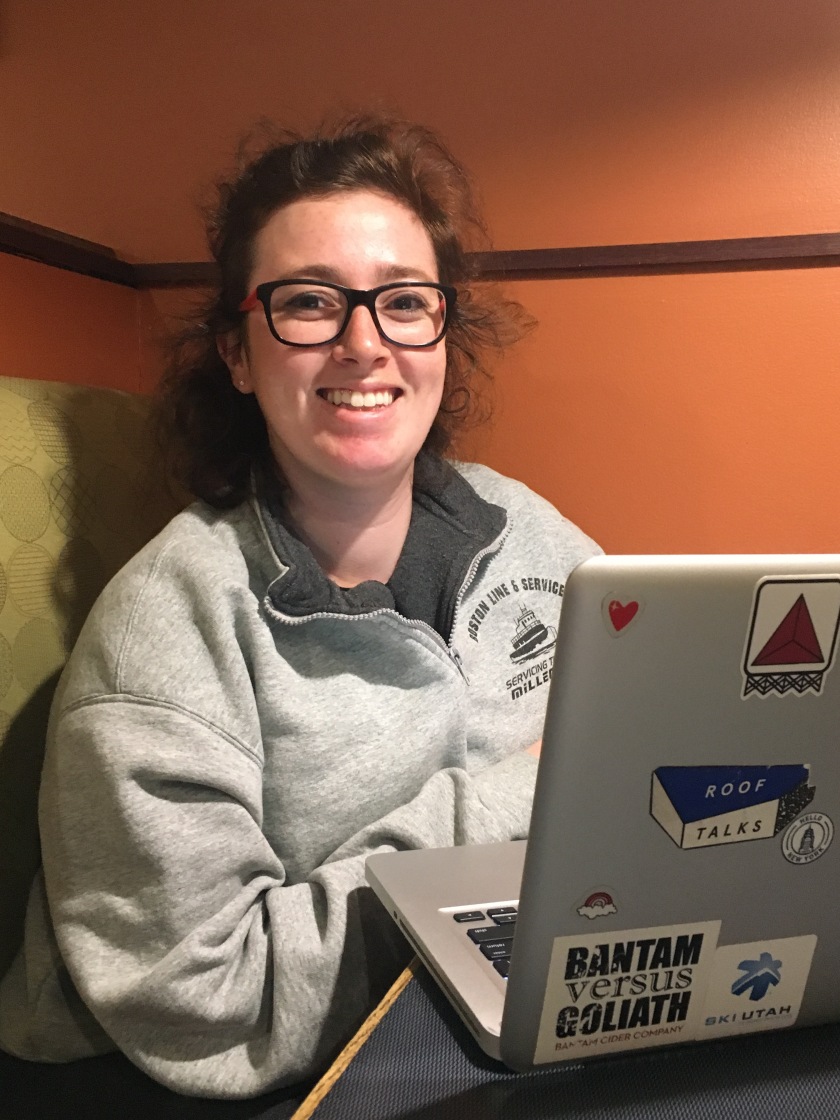

When Julia Cooper first walked through the glass doors of Northeastern’s University Health and Counseling Services (UHCS), the fourth-year psychology major was seeking relief from a depression that had settled like a leaden shawl around her shoulders. Cooper, despite struggling severely at the time, held out hope for her appointment with a behavioral health clinician.

And yet, behind closed doors, Cooper’s initial optimism turned quickly to dismay when she said the counselor started asking unsettling questions.

“She asked why I felt depressed and, when I told her I didn’t know, she said I should figure that out before seeking therapy,” Cooper recalls, voicing anger at how the appointment conveyed to her that clinicians employed by the university could offer little by way of real support.

The rhetoric its clinicians espoused then and in appointments with other students that Cooper has since heard from, she says, reflected a counseling center understaffed, overwhelmed and altogether unable to appropriately address the concerns students were carrying through its doors.

Instead of guiding her through steps to see a counselor on campus, the clinician seemed immediately fixated on leading Cooper off campus for help, looping in a referral coordinator to establish points of contact in the counseling community beyond campus.

“I was only taking three classes at the time and not working but the referrals they gave me only had openings during my class times, or were no longer practicing,” says Cooper. “I’m lucky enough to have good health insurance so I found therapy on my own.”

Since her experience, Cooper has begun to view the resources on campus – specifically the school’s short-term approach to counseling – with a more critical eye, joining mental health advocacy club Behind the SMILE and pushing for an infrastructural shift in how the university is addressing students’ mental health issues.

Northeastern currently utilizes a “short-term therapy” model, which limits students to seeing a therapist for six to 10 visits, or up to a semester, then refers them off-campus. It’s far from the only university to do so, but with surging demand for services forcing appointments to be spaced out to a month apart, semesters often run out before 10 sessions can even take place.

A 2014 survey of college counseling centers sponsored by the American College Counseling Association (ACCA) found that 30 percent of centers limit the number of counseling sessions students are allowed, while 43 percent don’t specify a limit on sessions but advertise themselves as short-term counseling services. Only 28 percent of centers tend to treat students until their issues are resolved in addition to referring them to off-campus resources.

Exacerbating Northeastern’s counseling issues is a drastic shortage of clinicians to treat the mental health issues of a huge student body. As per UHCS’ website, only nine permanent behavioral health clinicians are on staff to address the needs of roughly 20,000 students, including graduate and undergraduate students, establishing a ratio of one counselor for every 2,222 students. That ratio surpasses the university average of one counselor for every 2,081 students referenced in the ACCA’s findings.

“The school most of all needs to hire more therapists, so that the ones they have are not too busy to give quality care,” Cooper says. “They recognize these problems and have the money to take those actions, so there’s really no excuse for why they haven’t yet.”

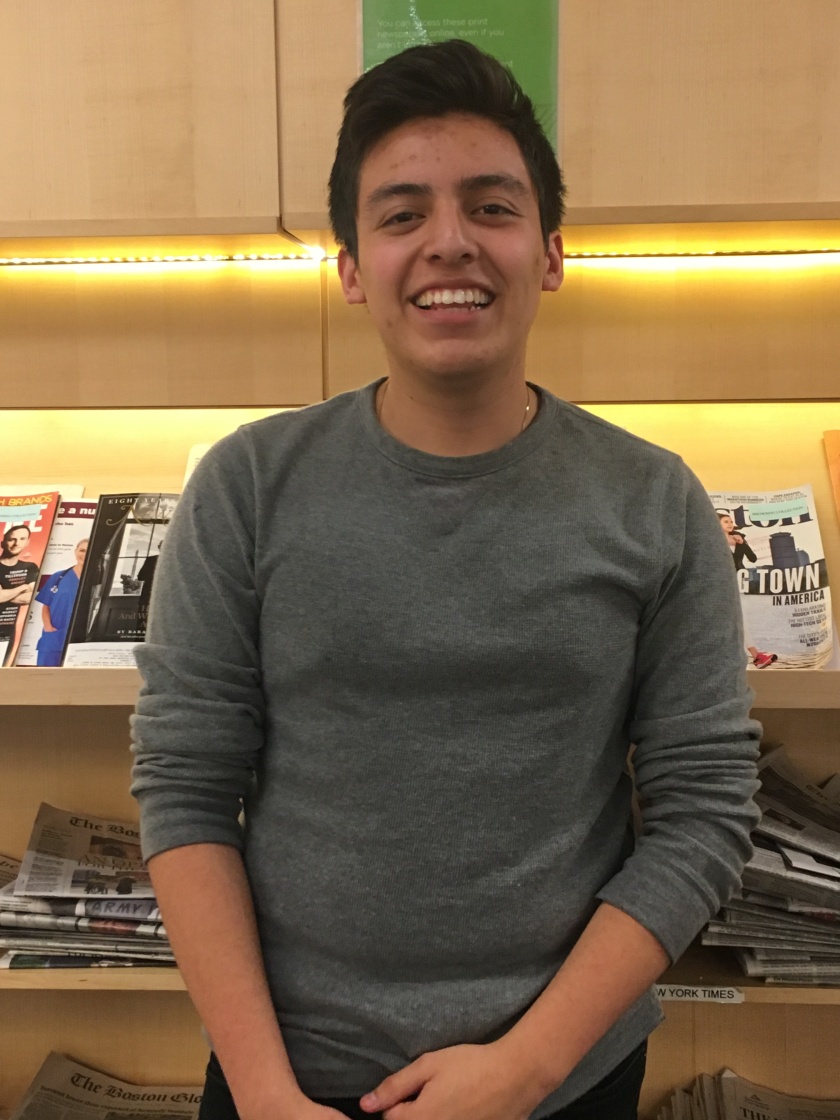

Joining Cooper in her criticism of UHCS’ setup, including its tendency to refer students out to external therapists rather than hire more clinicians to treat students on campus, is fourth-year human services major Laney Chace, also involved in Behind the SMILE.

“What I think is particularly problematic [about the short-term therapy approach] is the fact that you can be set up with a different therapist every time you have an appointment at UHCS so you really have no chance to build up any rapport with the person you’re seeing,” she explains. “Then you have to leave and start over with a new person.”

Chace echoes Cooper in identifying flaws in the referral process as well.

“The lists of referrals are not updated,” she says, meaning students already in crisis are often directed toward long-term counselors no longer practicing in the area or not open to taking multiple types of insurance. “Using it, people are often not able to be hooked up with a long-term therapist.”

Chace and Cooper, aside from being far from alone in voicing frustration by UHCS, are just two students among of an increasing number who feel failed by the current state of resources.

American colleges and universities across the board are experiencing a rise in demand for counseling so dramatic that experts, including Dr. Gregg Henriques, consider higher education to be in the midst of “a full-on mental health crisis.”

Henriques, a psychology professor at James Madison University in Viriginia who has written multiple articles for “Psychology Today” about how mental illness is mushrooming on college campuses, says that colleges are growing steadily aware of data that indicates a 300 percent increase in visible mental health problems in college students over the past three years. Cases of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, self-injury and suicidal ideation are all on the rise – and administrations know it. What they’re doing to combat the issue, however, is a different matter entirely.

“The administrations do not want lots of attention drawn to mental health issues or to talk about any numbers about their own institution,” says Henriques by phone, of the culture around mental illness that many school employees perpetuate. “They downplay or are reticent to disclose if there has been a suicide attempt.”

Henriques says that, often, colleges’ unwillingness to devote time and resources to combatting mental health issues comes down to fear of bad press.

“No one wants to say, “Hey, come to JMU, this is our suicide rate,’” he says.

Much of aiding students on campus comes down to reforming administrations’ faulty belief that increased rates of mental illness on their campus reflects a singular failure on the part of their school’s academic systems, rather than a complex mix of societal and individual conditions.

“You have to try to reduce some stigma around suicide on campuses,” says Henriques. “We also need to be working on educating people about emotions and about optimal mental health versus what is mental illness… I think psychology has done a very bad job, and psychiatry has done a worse job, of helping people understand what I call the ‘neurotic conditions,’ which are anxiety and depression, and living in stress, dysfunction and relational conflict. These are the things that are pressing the university counseling centers.”

Henriques impresses that short-term therapy mechanisms are an ineffectual, sometimes harmful approach to “Band-Aiding” mental health issues in college student populations. The accelerating rates of mental health crises on college campuses, he says, suggests a need for from-the-ground-up reform.

In pushing for better treatment of mental health issues on campus, Henriques accepts that some universities will never devote adequate funds to establish long-term counseling for students on campus. However, he insists that the need for better resources is growing – and universities who don’t pay attention to the data and advice of mental health professionals risk increased rates of suicide on their campuses.

“We need to think about a socially coordinated move,” Henriques says, involving not just counseling services but higher education as a whole. “We need community-wide initiatives to spread awareness, centers for well-being on campus, educational models for thinking about well-being – that’s how you start establishing a culture of care.”

At Northeastern, Cooper and Chace hope student groups like Behind the SMILE are helping students in mental health crisis, and that such students are benefiting from initiatives like the student-run textline Lean on Me Huntington that launched this spring and an American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP)-affiliated Out of the Darkness Walk for Suicide Prevention held on campus earlier this month.

However, both indicate a sense of disappointment in UHCS’ rhetoric and treatment of students coming in often in states of severe distress.

“It was about two years ago when I went and I was super depressed,” recalls Cooper of the experience that opened her eyes about the center’s inadequate resources. “That appointment was the only time I left my bed that week – I don’t think it hugely impacted my mental health only because I knew what [the counselor] said wasn’t true, because I already knew a lot about depression and mental health, but I don’t think I would have sought therapy if that weren’t the case.”

It’s dangerous, Cooper says, for a school’s counseling services to send inaccurate or half-formed messages to students struggling with mental illness.

“Therapy was the main thing that helped me recover from depression,” she says. “I don’t know where I would be if I thought I had to figure out depression on my own before going.”